#31. Waiting in public

February 17, 2026

In Part 1 (#29. You can’t invest in generations), I argued you can’t invest in generational timelines. In Part 2 (#30. Time vs. human nature), I argued time breaks under delegation. Specifically:

Delegated decision-makers face consequences long before investments resolve, despite institutional patience and conviction. Career risk arrives early. Benchmarks are observed constantly. Relative performance is visible immediately. Interim marks are treated as signals. Under these conditions, waiting is not neutral. Waiting becomes risky.

The reason is that delegated decisions in any context - investment, consulting, everyday employee decisions - add a second objective to the decision: staying employable and credible while the results come to fruition.

Hypothesis 2: Delegated decisions are governed by personal risk

Not controversial, but underexamined. This behavioral reality explains the difference between claiming a long time horizon and being structurally able to act on one. A delegated decision-maker is not optimizing for being right. They are optimizing for being right before they can be fired.

There are many examples of people taking unusual bets, taking a stand against their superior, or whipping out the ol’ steely eyed “trust me.” But those personal risks are palatable when the payoff arrives quickly. The longer the timeline, the more painful waiting becomes. And, thus, the less likely the delegated decision-maker is to diverge from the safe pick. It doesn’t matter if the potential payoff is massive. Waiting under a disagreeing watchful eye is excruciating and, sometimes, fatal. Of course, pressure is not purely corrosive. Pressure disciplines capital. The challenge isn’t eliminating pressure. It’s distinguishing between discipline and capitulation.

Aversion to personal risk is why organizations slow as they mature. That’s why the annoying start-up fundraising question “Why can’t Google just do this?” becomes easier to answer as Google grows older and more complex. Layers of delegation and complexity push decisions toward safe, consensus bets. “No one ever got fired for hiring McKinsey.” Soon, you end up with entire organizations and industries regurgitating the same ideas exactly *because* they are the same ideas. Justifiable loss is tolerable; embarrassing loss is not.

Consensus capital

In the late-1990s, value and growth stock returns diverged hugely as internet names like Cisco, Yahoo, and AOL ascended. Meanwhile, value investors held companies like Berkshire Hathaway and Coca-Cola, believing earnings power, balance sheet strength, and valuation spreads (between value and growth names) would drive long term returns, as they historically had. Soon, value investors found themselves in the position of being unexpectedly counter-narrative. Growth dramatically outperformed, and value underperformed, for multiple consecutive years. Even as value stock fundamentals largely held, valuation spreads between value and growth ballooned. What followed was a breakdown of the owners’ decision-making process out of fear of being different.

The thesis didn’t break. The timeline did. The payoff moved further out, and that duration increased pain immediately. The institutional cost of waiting rose faster than the benefit of being right.

The longer divergence persists, the more reputational and career risk dominates the expected value. Under those conditions, even correct long-horizon theses become institutionally expensive to hold.

Value investors didn’t enter 1997 believing they were making a non-consensus bet. In hindsight, what could they have done? You can’t remove this risk entirely (that’s kind of the point and benefit of making non-consensus bets). There always has been and always will be pressure on non-consensus decisions. But true long-term bets must be engineered to survive. If you are unwilling to be wrong publicly for three years, you should not run concentrated capital. Survivability is not accidental. It is designed. How?

Bound the divergence. How wrong are you willing to look? For how long?

Define interim proof. If price is not the scorecard, what is? (earnings power, clinical trial progress, cost curves)

Hedge for survival, not optimization. Any hedge that protects against the widest underperformance will trim the upside. The goal of a hedge here is not to maximize return. It is to buy time. Trimming upside is a worthwhile price for survival. Perhaps with iterative success and trust, that hedge can become smaller.

Firstly and lastly, none of these ultimately matter much if you don’t communicate the thesis and mitigation measures with the capital owner.

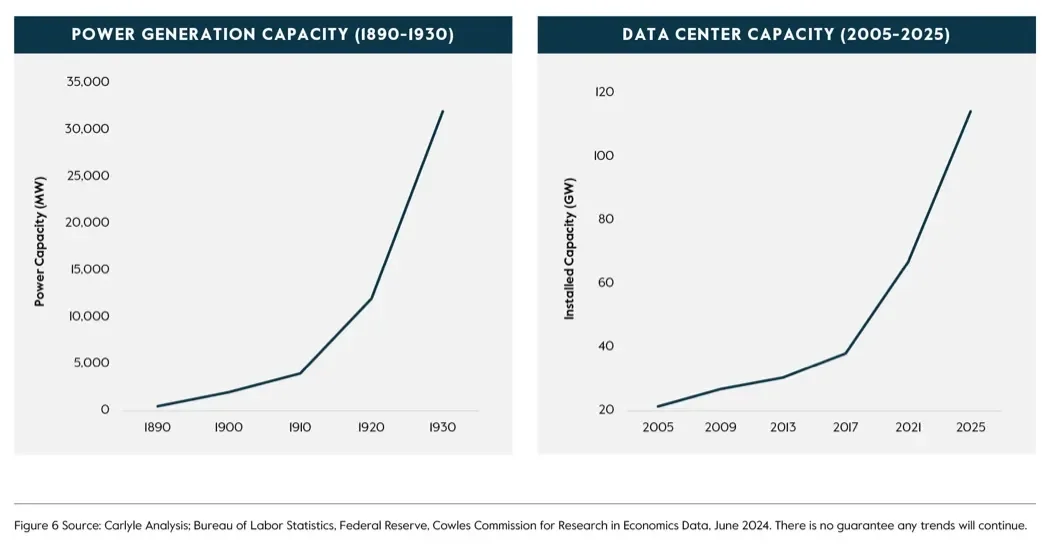

An interesting counterexample exists in modern markets. Whereas value investors didn’t expect to become non-consensus in 1997, data center investors likely didn’t expect to become *so* consensus in 2026. AI infrastructure demand has driven data center buildout to a pace comparable to electricity buildout boom in the early 20th century. What began as a differentiated thesis has blown past institutional default positioning to downright frothy.

Different risk, same mechanism. In one case, you’re punished for waiting too long for fundamentals to reassert themselves. In the other, you are rewarded so quickly that you forget to ask whether the thesis has already resolved. Delegated systems struggle in both directions. They’re pressured to abandon correct ideas when pain lasts too long and they overstay correct ideas when consensus arrives too fast.

The danger is not being early or late. The danger is allowing narrative coherence to substitute for system discipline.

Engineering survivability

What does praying at the altar of narrative coherence look like? Herding, indexing, buying out of fear-of-missing-out and selling out of fear. This law of motion drives position and sector rotation, shortens hold periods, and heightens volatility. I wrote some time ago that Jordanian Minister of Finance H.E. Mohamad Al-Issis argued that the world is no longer driven by cycles, but by shocks (see: #27. Collective Illusion and Resilience). The same is increasingly true of investing.

Nothing that requires prolonged defensibility can survive the pressure of regret.

So what endures? Not firms. Not decisions. Not people. Systems. So what are systems made of?

Delegate incentives. Incentives dictate actions. If your job can be questioned before your bet resolves, you don’t actually have a long time horizon. Long-term capital requires the willingness to be visibly wrong for years, not quarters.

Pre-mortems. Assume this bet fails. Answer why.

Evaluation windows. When will you know whether you’re right or wrong?

Feedback loops. What proves progress besides stock price or valuation?

Intervention thresholds. How much divergence are you willing to stomach before you act? Remember waiting is expensive.

Positions and allocations compound over quarters. Systems compound over decades. Over generations. They absorb error without collapsing, breathe without narrative coherence, and raise the friction to react. The goal is to structure accountability around resolution, not discomfort.

For so many, being a better long-term investor is not picking better ideas or being more patient. It’s designing for turnover and pre-committing to discipline.

If time breaks under delegation and capital minimizes regret, then only systems designed to withstand regret pressure can compound across decades. That’s where long-term advantage actually comes from.

Endurance is a design choice.